- Home

- Emily Paull

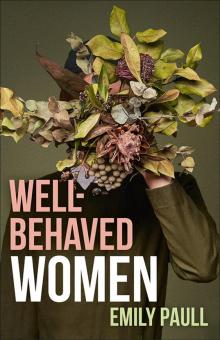

Well-behaved Women Page 3

Well-behaved Women Read online

Page 3

Miss Lovegrove sighed, and she threw her hands up in exasperation. ‘You young women, you come through this program and you all think you’re going to get to where I got, and it’s going to be like a fairy tale. It’s not a fairy tale. This is an industry where to make it, and I mean to really make it, as a woman, you have to do some despicable things.’

‘Then you should be helping us to change that. You’re our teacher. It’s your job.’

‘No. My job is to help you realise that the world is sometimes a dirty, ugly place. I don’t have to help you students, and I especially don’t have to like you. You did well tonight because I helped you access something real. You’ll be thanking me for the rest of your professional life.’

‘I think you’re wrong about that,’ I said.

In the half-light of the empty stage, she looked much older than usual.

‘Haven’t you worked it out yet, Nicole? I don’t give a damn what you think,’ she said, and walked away, leaving me alone on the naked stage.

CRYING IN PUBLIC

June

The local football team were arriving for their pre-training dip in the sea as I pulled up. Otherwise, the car park at Floreat Beach was empty. At the far end, all of the green bins were congregated and ready for rubbish collection, though the lid on one had fallen open and crows had spread the remnants of someone’s fish and chips all over the grass. I stayed in my car until the footballers had passed. Some of them were barely wearing anything, just tiny black Speedos, and goggles on the tops of their heads. I looked at them the way a cat looks at a dog, only dimly registering that a year ago, I would have been flipping my hair and flirting. Instead, I pulled the hood of my jacket up over my greasy hair as I got out of the car, and leaned on the driver’s side door, staring out to sea.

It was good to be cold. It was good to feel like the ends of my fingers and nose could turn to ice at any moment. The jacket had been in my car, forgotten after a trip to the gym and never washed. The cotton sleeves were sticky where I’d leaned in something, and there was a hint of old sweat under the arms. The worst part was that I didn’t care.

My grandmother arrived at eight, swinging her blue Prius into the spot next to my beat-up Mitsubishi. She parked, and sat in the driver’s seat for a moment to tie a red scarf around her head and put on her sunglasses. She looked like a glamorous pirate, rather than a seventy-year-old breast cancer survivor.

Hoisting herself out of the car, she kissed me on the cheek. ‘Oh, my aching knees. I’m too old for this, girl.’

As she hugged me, my limbs felt far away and bruised. A wave of relief at her presence threatened to crush me, and I fought the urge to cry. Grandma Mimi picked a loose hair on the arm of my jumper and raised an eyebrow as she took me in.

‘Shall we walk? Or shall we let those West Coast Eagles have the whole beach to themselves?’

Her South African accent was never more pronounced than when she was teasing. In our family, she was the grandparent most likely to give presents that made noise, or flashed, or made my father crazy. She was the one who had seen the world, the one who gave the best advice. According to my mother, she was also the one holding the purse strings, but she had never cared much for expensive things. When something went wrong, Grandma Mimi was always the person I called.

Something had been different this time around. When Mark had told me that he was moving out, I had picked up the phone and looked at her number in my address book, but shame had held me back. Like a coward, I had written the words in an email; and instead, it was my mother who came around and helped me to move all of the clothes and books he’d left behind into the wardrobe in the study, so that I didn’t have to look at them. Perhaps it had hurt my grandmother’s feelings to have found out in such a roundabout way, but in grieving for my first big love, I had been too selfish to consider how this change in our roles could knock everything out of synchronisation.

I had not seen Mimi or Mark for a month. It was Grandma Mimi I missed the most, but Mark whose presence was still the more noticeable, for there were traces of Mark in my house, in my routine, in the bills that came in the post, and on my body. The longer I waited, the more I felt ashamed to show my grandmother how much of myself I had given to a man who had proven himself to be unworthy.

At the beach, we ambled along the path without speaking, watching a fitness group run crazed laps around their orange cones, distorted dance hits piping out of an iPhone. Grandma Mimi did not bother to conceal her laughter as a lithe, tanned woman in a sports bra and shorts flipped a tyre end over end in the sand.

‘You could not pay me a thousand bucks to do that.’

‘I couldn’t pay you a thousand bucks, anyway,’ I said.

She frowned, and pinched at my stomach through my clothes. ‘You eating all right, girl? Your parents helping you out a little bit with the rent, now old what’s-his-face has chuffed off?’

I tried to smile. ‘I’m getting by.’

‘None of that two-minute noodles nonsense?’

‘Only occasionally.’

‘Occasionally? You want noodles, you come to my place, and I’ll cook us a stir-fry with lots of fresh vegetables and chili. Those pot noodles you buy at the supermarket have less nutritional value than my shoes.’

My fake smile became a laugh, but laughter quickly turned to tears, and I stopped walking to lean against one of the trees that lined the footpath. I couldn’t breathe.

Grandma Mimi pulled me out of the path of a cyclist and steered me towards a nearby bench. She pulled a packet of tissues out of her pocket and waited, the set of her body signalling that she would wait for an explanation as long as it took.

‘Have you heard from him?’ she demanded, hands on her hips. ‘Does he want his things, or shall we bring them out here next weekend and give them to the sea?’

I nodded. ‘He’s moving in to her place. He wants his TV. And he wants me to sell the rest of the furniture and give him half the money.’

‘Pah!’ she cried, startling a passing jogger. ‘He can get stuffed. He doesn’t have a right to anything in that house anymore.’ I wiped at my nose. ‘Maybe not, but he’ll want that money. He’s starting a new life.’

‘Well, he’s a slut,’ she said, decisively. ‘A faithless slut.’

July

At the bright-coloured café, Grandma Mimi ordered two hot chocolates with extra marshmallows, not even pausing to ask me if it was what I wanted.

‘Sugar is good for heartbreak,’ she said to the young man taking our order.

He glanced at me self-consciously, and I slouched a little lower in my chair.

Sipping at my drink, I could feel her watching me, could tell by the miles-away expression on her face that she was weighing up which piece of wisdom she wanted to bestow on me.

‘Did I ever tell you about the man I almost married, before I moved to Australia?’

I shook my head. I tried to picture her with anyone other than Grandpa Bill, and failed.

‘Don’t look so shocked, girl! We had been very happy together for two years. He was my first love, and we got engaged when I was twenty. My cousin Celia, who was also my closest friend, threw me this great big engagement party at her parents’ house. I felt like the Queen. I bought a new dress, I had my hair done. My mother let me wear her pearl earrings.’ I pushed a marshmallow around in my glass, trying to make it melt faster. ‘So, what happened?’

‘Well, I was so busy being the hostess and having everyone pay attention to me that I didn’t notice my cousin and fiancé getting on like a house on fire. They sat talking on a bench in the garden all night long while I flitted around offering cocktails to my parents’ friends. A month later, they both came to my house. When I saw them together, I knew something was going on. They told me they had fallen in love—that they believed they were soulmates. They said they both loved me very much, and that it was terrible timing, but they wouldn’t give one another up, and they hoped I would forgive them. It hurt like th

e devil, but I stared them both down and said, “Well now, that’s it. I’m emigrating to Australia and neither of you selfish pigs will ever see me again.” So I did, and they didn’t, and then I met your grandfather, and it wasn’t until I was quite a bit older that I realised that if I hadn’t had my heart broken, I never would have.’

‘Did you forgive them?’ I asked.

‘No. And I don’t think I ever will. But that’s not the point.’

She sat back in her chair, and her gaze drifted around the room as if she were lost in memory. I pictured her at twenty, that same indomitable smile, those dark charming eyes. I tried to imagine the calibre of man who could have dared to leave her. I wondered if she’d cried in front of them, or if she’d waited until after they’d gone. The day Mark had told me he was leaving, I’d tried so hard to hold myself together that the sobs had ended up forcing themselves out between my teeth like hiccups. For him, it had seemed no worse than a trip to the dentist—uncomfortable, unavoidable, but best to get it over with. I remembered the way he’d kept scratching at the end of his nose, as if something had bitten him there. Sitting in the café with Grandma Mimi, I realised I could no longer remember exactly what he’d said to me. Had he said ‘I’m leaving you’, or had he gone with something more clichéd, like ‘I can’t do this anymore’? Perhaps he’d said it outright—‘I am in love with someone else.’ But I had the distinct feeling that it had been up to me to say that, and he had been relieved to find that part of me already knew.

It was the tyranny of Facebook. I was no longer Mark’s girlfriend, but because we had so many friends in common, I could not go online without seeing they had bought a house together in Jolimont, or that Katrina—beautiful, vicious, predatory Katrina—was now wearing the diamond ring I’d seen in his bedside drawer.

The syrup in the hot chocolate had settled at the bottom of the glass, so I stirred it quickly, afraid of the sound of my spoon against the side of my mug. I did not want to be too noisy, take up too much space, be too much of a nuisance; give anyone another reason ever again to choose a girl like Katrina over me.

When I looked at Grandma Mimi, she was miles away too. There were the ghosts of tears in her eyes.

August

I took a week off from work in August to take back control of the apartment. The only furniture I had left was old, though Mark had generously let me keep the bed we’d bought together. I might have put it on the kerb out of spite if I’d been able to afford another one, but as my finances currently stood, I’d had to resort to changing the sheets.

On my second day of leave, Grandma Mimi surprised me by arriving with a roll of yellow garbage bags and a selection of empty boxes.

‘Have you heard of this Marie Kondo woman?’ she said, instead of saying hello. ‘We’re going to KonMari your house.’

We emptied all of my clothes and shoes and handbags into a pile in the middle of the floor, then slumped, exhausted, on the couch. Grandma Mimi’s face was pale, and under her glasses I could see deep, dark bags.

‘This one’s nice,’ she said, pointing at a blue dress with the toe of her sneaker. ‘How come you never wear it?’

I shrugged. ‘Forgot that I had it, I guess.’

Grandma Mimi rolled her eyes. ‘Well, forget all of this spark joy nonsense. If I’d known you had so much stuff, I would not have suggested this. But let’s clear out the cupboards anyway.’

She sat on the couch with a cup of Lady Grey nestled in her lap while I sorted through my things. I got rid of things that didn’t fit, things I didn’t like, things I’d never got around to mending. By the end of the afternoon, a big yellow garbage bag full of clothes sat waiting by the front door, ready to be donated. When all of my clothes had been neatly folded or hung in the wardrobe, something about the apartment felt different. It felt, for the first time, like it was mine.

Grandma Mimi took the bed that night, while I slept on the couch. I slept better than I had in weeks, timing my breathing to the soft purr of her snoring, only just audible through the bedroom door.

September

No matter what we did, we always ended up back at the ocean. The sea breeze was in our blood, she said, and it was why we were so salty. The turning season seemed to revive Grandma Mimi, and on our first Sunday morning walk in September, it was she who set the pace.

At the playground, screaming children played a game of chasey. Grandma Mimi pointed to the monkey bars and said, ‘Do you remember when you used to be afraid of those, Sara?’

I wondered if I did, or if I only thought I did because she had told me so many times. I remembered the strength of my belief that my hands were not strong enough to propel me across, and so I nodded.

Laughing, she strode over to them and walked along underneath, her hands touching each bar. ‘Not so hard now, an old bird like me can do it.’

‘You’re not old, Grandma Mimi!’ I protested, hoisting myself up to stand at one end, judging the distance to see how far out I might be able to jump.

She raised her eyebrow, shaking her head. ‘You always were a bad liar, girl.’

Giving up on the monkey bars, I turned to face the ocean. ‘Do you have your bathers with you?’

‘Never seem to take them off these days.’

‘Shall we see how cold it is, then?’

I surprised myself with the suggestion; it was still far too early, far too cold, for a proper swim. But the process of healing was almost complete. All that was needed now was to wash myself clean. And Grandma Mimi had gone through it with me.

As we shimmied out of our joggers and tracksuit pants, grinning at one another, I had an eerie sensation that it was not the seventy-year-old Grandma Mimi by my side at all, but rather the twenty-year-old version I had seen in photographs, her hair a tangled braid down her back and her lips painted brick red.

We shed our clothes, our pasts, our betrayals—then we linked hands and raced towards the waves.

A MOVEABLE FARCE

Michael had been living in Paris for almost three months at the time of the attacks. He still thought of Cottesloe as home, even though he had sold his bed and his PlayStation and his car in order to move away from it.

He was the uncouth Aussie, the foreigner. He was only just learning not to flinch at the sound of his own nasal vowel sounds when he spoke, to enjoy hot bitter coffee with lots of sugar, and to exist on a diet of toast and boiled eggs in order to pay his rent each month. Michael had pictured an apartment with white curtains that looked out over the Seine, where he could sit in his window seat and write pages of inspired prose as the sun came up. He had imagined himself as Hemingway, drinking whiskey and soda in a wood-panelled bar until all hours of the night, and meeting women—so many women. But what he had ended up renting did not even have a glimpse of the Eiffel Tower. It looked onto a grey damp alley filled with metal bins, where tomcats fought in the night unless one of the neighbours thought to get up and empty a bucket of water onto them. He had not been able to afford to drink in bars. He had not met any women who found him interesting. And he wasn’t getting any writing done.

Instead, he was working in a café in a street popular with tourists. The café was owned by a Tasmanian named John— so he had come halfway around the world to do something he could have done at home. The few French customers they had thought Michael’s accent was amusing. They loved it when he said things like ‘Yeah, nah.’ Michael had introduced some of them to the concept of the flat white, but they found it a poor substitute for a latte.

It was late one night when he sat down in front of his laptop, staring down the cursor. He’d thrown open the doors to the small balconette, despite the alley outside smelling like a mixture of human and feline piss. Through earphones, he was listening to a radio station half the world away, where it was the next morning. At the top of the hour, a news bulletin sounded. The sullen, sombre voice of the newscaster broke through his procrastination.

‘Breaking news out of Paris, where we are hearing report

s of a mass shooting inside the Bataclan theatre …’

Michael had the sensation of having been pulled out of his own timeline, and he ripped the earphones out of his ears. Outside, sirens were wailing, but far away. He felt suddenly exposed, as though a person were standing behind him, but when he turned, there was no-one there. He ran to the balconette and hurried to close the doors. As he yanked at the curtains, he glanced at the building across the alleyway and locked eyes with the woman who lived there, doing the same thing. She had a small child in her arms. She was whispering to him, rocking back and forth and trying to make him sleep. She looked terrified. She wrenched the curtains shut and closed Michael out.

His mobile phone was almost out of battery, rattling with so many text messages and missed calls that it had spun its way across the kitchen table and was perilously close to the edge. Nineteen missed calls from his mother; two calls and a text from his dad in Sydney. As he picked it up, it began to ring again, and the ID on the screen brought up a smiling photograph of his mother in her gardening gloves, holding a pile of mulch out to the camera to show a wriggling earth-worm in the middle of her palms. He answered before the first ring was complete.

‘Mum, hi,’ he said, breathless. ‘I was writing. I only just heard.’

She was crying. ‘Thank God,’ she managed to say. ‘Oh, thank God.’

Michael was filled with heavy guilt. Her only son was on the other side of the world, where something terrible was happening, and he couldn’t even do something as simple as answer his phone.

‘I’m so sorry I didn’t pick up.’ He wanted to cry too, so he kept his voice soft, sneaking the words around the lump in his throat.

They spoke for a while, or rather, he listened while she sobbed and told him all the awful things they were saying on the news. The stadium, where the French President had been watching a soccer match, had been targeted by a suicide bomber. On the Rue Alibert, men with semi-automatic rifles had forced bars and nightclubs to close their customers inside. Fifteen people eating dinner at a Cambodian restaurant had been killed. Five more were killed a few streets south. Around midnight, three gunmen had entered the Bataclan theatre and fired indiscriminately on the crowd gathered there to watch the Eagles of Death Metal. The death toll there was still in flux.

Well-behaved Women

Well-behaved Women