- Home

- Emily Paull

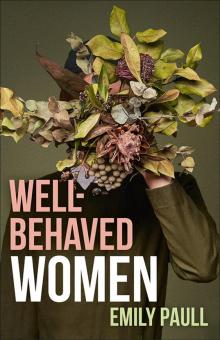

Well-behaved Women

Well-behaved Women Read online

First published in Australia in 2019

By Margaret River Press

PO Box 47

Witchcliffe WA 6286

www.margaretriverpress.com

email: [email protected]

Copyright © Emily Paull

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Enquiries should be made to the publisher.

Cover design by Debra Billson

Edited by Laurie Steed

Printed in Australia by McPherson’s Printing Group

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia

This publication has been made possible with funding from the Department of Local Government, Sport and Cultural Industries.

ISBN: 978-0-6486521-1-3

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Emily Paull is a former-bookseller and future-librarian from Perth, who writes short stories and historical fiction. Her work has appeared in numerous anthologies as well as in Westerly journal. When she’s not writing, she can often be found with her nose in a book.

For my mum, Megan,

who makes everything better, always

CONTENTS

The Sea Also Waits

Miss Lovegrove

Crying in Public

A Moveable Farce

Sister Madly Deeply

Dora

A Thousand Words

Down South

From Under the Ground

Nana’s House

Picnic at Greens Pool

Font de Gracia

The Things We Rescued

Pretending

The Settlement

Versions of Herself

The Woman at the Writers Festival

Notes on Previous Publications

Acknowledgments

THE SEA ALSO WAITS

Six nights ago, my mother disappeared into the ocean.

This wasn’t unusual. She was a free diver. She had been submerging herself for as many years as I had been alive. There were moments I was almost convinced that she loved the ocean more than she loved me.

She’d suggested that we take the tinny out into the bay, put on our wetsuits and dive in the last warm shoals where the reef drops away. She sat on the bench in the boat, gripping her nails into the wood of the seat to stop from bouncing up and down. I was tired, and steered the boat with a degree of disinterest, drifting this way and that, out over the bay.

Finally, she held her hand up to stop me, but her eyes stayed on the water. ‘Here,’ she said. ‘Damian, stop here.’

I cut the motor. The silence was sudden, as if a lid had been put onto the world. There was only the splashing of waves against our aluminium sides, like a heartbeat. She slipped off her dress; it pooled in a puddle of fabric on the boat’s floor. Underneath, as always, were her bathers. The boat rocked side to side as she slipped into her wetsuit. It went on like a second skin. Free-diving wetsuits are thin and low-buoyancy to aid the diver’s descent. Hers was a deep shade of blue, which made her hard to see once she went under. She loved the idea that her wetsuit might make her invisible. She’d been wearing it when she set the record for the deepest free dive in Australia. That time, there had been a rope, to measure the depth and tether her. There were judges, and lifeguards, and other divers. This night, there was only me, but she wasn’t going for the record. She’d dive a few times, scratch whatever itch she had that needed to be scratched, and we’d go home for dinner. Zipping the suit up, she looked at me and grinned. ‘Are you coming in?’

I shook my head. It had been weeks since I’d had time to dive. I was studying; I had decided to become a journalist. I wanted to get into university, but I’d been homeschooled for so long that it sometimes felt as if my homework were written in another language. Once, I had wanted to be a world-famous free diver too, but the idea seemed less and less possible, the longer I spent away from it. I’d started to think of the things my mother and I had done as stories, things that had happened to other people. Surely we had never floated face down in the Garibaldi’s swimming pool for nine minutes. Surely we had not flown to Greece to compete in the world championships while other kids were learning their times table. Surely we did not take the tinny out into the bay in the middle of the night in order to swim to the bottom of the ocean with weights around our necks.

Yet, there we were.

She slipped over the side, and I picked at a fleck of paint that had peeled off the inside of the boat, trying to make the biggest piece possible. It was like peeling the scales from a fish. Mum reached into the boat for her goggles, her hair slicked back. In the dark, it looked like seal fur, her eyes now brighter with her eyelashes webbed together. She smiled; her skin had turned pale where it reflected the water. She lay on her back, tucked her knees up to secure the monofin. I leaned my head against my arms on the side of the boat, and the tinny tipped slightly towards her, bringing us face-to-face. She reached out and pressed her sodden hand to my cheek.

I couldn’t wait for her to exhaust herself so that we could just go home, and I could do my homework and then we could both go to bed.

My mother began her breathing exercises, taking short breaths, and then expelling the air from her lungs in longer and longer bursts. It was a process called ‘breathing up’. It brought to mind the way the body fought for oxygen as you raced back to the surface. The sounds she made were alarm-ing. It was like an asthma attack. It was essential that I not talk to her while she readied herself, or she’d lose count and have to start again.

Finally, she was ready. She nodded, signalling that I should start the stopwatch. My mother tucked her body up, and then she was under; the tiny concentric rings where the water had been displaced, the only marker to say where she’d been. My job was to wait, to watch the seconds tick away, and be ready with the towel. Already, I was thinking about the feast we would eat. It was a warm night; my mother was fond of barbecued pork drizzled with sweet, thick sauce. The dives always made her ravenous.

The bay was calm and silent. I saw boats on the far side of the bay bobbing up and down in the marina. So many this year, and more and more were staying. The holiday bungalows would soon be gone, replaced with reclaimed timber houses three storeys high, with tennis courts, swimming pools, and glimpses of the ocean from the balcony.

Once, when I was younger, my mother had taken me to practise in the bay. It was full of vacationers in bright new swimmers. A lady doing the breaststroke had heard us breathing up, and thought we were drowning. She swam over to us on her back, waving with her closed fist to signal the lifesavers. She was a very fit lady, but she’d struggled, kicking her legs at odd angles, trying to hold both me and Mum up at the same time. I’d struggled against her grasp, but she began to sink and my mouth filled with water; there was no way for me to explain what she was doing. Mum had continued her breathing, a wry, bemused look on her face, allowing the lady to hold her up by one armpit. By the time the lifesaver paddled out to us on his foam board, Mum was ready to dive. Instead, she blinked as if she were emerging from a dream, looked at our would-be rescuer and said, ‘Oh. Hello.’

The woman looked confused, and slightly waterlogged, her chin disappearing beneath the water in an attempt to hold us both up. Mum was kicking again now, her powerful fins doing some of the work, and the lady let go slowly, her hand drifting back to her side. The lifesaver adjusted the white ties at his throat and laughed.

‘Hello, Katerina,’ he said, shaking his head. ‘Teaching Damo to dive, are you?’

&n

bsp; Mum grinned. ‘How are the kids, Shane?’

The lady looked between Mum and the lifesaver in dis-belief. ‘Excuse me,’ she said, sounding a little woozy. ‘Could someone tell me what’s going on?’

He chuckled. ‘You’ve just rescued one of the world’s most famous free divers. I don’t believe you could drown Katerina if you tried. It’s widely believed she’s part-fish.’

Mum pretended to take a bow, lowering her face to the water.

‘But she was choking! I heard her. And the boy …’

‘I was clearing my lungs, preparing them to take in enough air to get me as far down into the ocean as possible.’

‘Don’t you think that’s a somewhat unsafe activity for a child?’

Shane chuckled again, bobbing on the wave atop his board, his shadow blocking the sun. The lady seemed in no mood to swim away.

My mother shrugged. ‘I asked him if he wanted to take up base jumping, but it seems the urge to free dive is in his blood.’

The lady made a scoffing noise deep in her throat and slicked back her hair, which was a green-gold shade that hinted at a home swimming pool. Her nails were painted a bright peach colour, and when she reached back I could see the parts of her shoulders where a racerback swimsuit had tanned onto her skin. ‘This isn’t a laughing matter.’

Mum reached out to pull me closer; the current had begun to take me out. ‘It really isn’t any of your business.’

‘Tell her,’ the lady demanded, turning to Shane, ‘that it’s dangerous.’

‘She knows it’s dangerous,’ replied the lifesaver. ‘That’s why she does it.’

I don’t remember what happened with the lady; whether she continued to argue with my mother or swam back to shore, disgusted with us and our devil-may-care coastal ways. Come the end of summer, she and her husband were gone. We saw them loading their minivan with bags on the driveway of one of the rental bungalows a street back from the beach. The lady’s racerback tan had almost gone, but when she reached up to tie her husband’s surfboard to the roof, her skirt rode up, and I saw a new tan line across the top of her thighs.

After that, we only ever trained in the evening, when most of the swimmers had gone in, and the smell of barbecues, and fish and chips, had drifted out with the sea breeze. The water could be extremely cold, but our wetsuits kept us warm for the most part, and as for Mum, I don’t think she felt anything except the sheer elation of once more being in the water. It was part of her; I could tell from the way she moved through it, as if it were moving through her.

I looked back at the stopwatch, and at first I thought I was reading it wrong. 20:05. That was more than twice as long as any other dive she’d done. I felt a great shout rising in my throat, and a laugh escaped my lips the way bubbles rise through the water. I went to stand, to call out to her that she’d broken the record. I peered over the side, but it was too dark. I couldn’t see the bullet shape of the top of her head as it charged towards me through the foam. There were no bubbles, no ripples; nothing.

The torch we used was by my feet in the boat. I strapped it to my wrist and turned it on, scanning the surface of the water for shapes. All the while, I was kicking off my shoes and struggling out of my shirt. I plunged over the side, still wearing my jeans.

It was cold and the water was weedy. My eyes stung from the salt, and while shapes loomed close as I paddled as deep as I dared without preparing, none of them was my mother. It was as if she’d never been there at all.

I kicked for the surface and dragged myself back onto the boat. We kept a short-wave radio with the first aid kit. My hands shook as I checked the batteries and tried to call in to shore.

‘Is anyone there? It’s Damian … My mum …’

The static on the other end was so loud that it made me jump. After a moment, a man’s voice came on. ‘Damian, it’s Shane. What’s the problem?’

‘Mum. She never came up.’

‘Okay, don’t panic. Where are you?’

‘On the reef … south side of the marina.’

‘Stay put, Damo, I’ll come to you.’

Shane’s skin had turned to leather from the sun, despite the stripes of zinc he plastered to his face every day of his life. His hair was surprisingly grey now that his cap was off. The inflatable raft bounced across the water as he charged towards me. My tinny rocked in the waves as he came closer. Beside him in the boat were two other lifesavers, a man and a younger woman, both carrying fins and snorkels.

Shane looked sick as he pulled up alongside me. His jaw was clenched, like he was holding something in his mouth. ‘We’ve called the coast guard. Told ’em Katerina’s not come up and to keep an eye out in case she’s been caught in a rip. Perhaps she’s already on a beach, and she’s looking for you right now.’

I nodded, and threw up a little in the back of my throat. Shane was already up and climbing into my boat. He grabbed me by the arm. ‘Do you have your gear in the tinny?’ I nodded.

He took charge and began clipping spotlights to the side of the boat, sending reams of light down into the water. I put on my wetsuit, not caring about the others around me as I stripped off my wet jeans. My hands were shaking so badly that I couldn’t do up the zipper at the back of my neck. I put on my fins and goggles. Shane took a line from one of the lifeguards and attached one end to my belt and the other to the side of the boat. I put the weights around my neck and tried not to think about what I would find when I went under. After a few breaths, I tossed myself backwards over the side.

It was disorienting at first, being back under the water after so many months away. My body remembered how to do everything, and it seemed to take control while my mind went on panicking and searching. There was seaweed floating everywhere, dark and creepy as it drifted about in the tide. I swam downwards, spinning around, looking for the slightest traces of her. It was strange. There didn’t even seem to be any fish.

I felt the water pressure increasing as I got deeper. The water grew colder. When I looked up, I could no longer see the bottom of the boat; when I looked down, there was nothing. But I was calm; being in the water had done that to me.

Shane tugged twice on the rope, and I began to swim up, following its line towards the surface. Every now and then, I stopped to depressurise.

It felt in those moments like I was looking back, taking a last glimpse of her and waving goodbye. The last thought I had as I ascended from the ocean was of our first dive together, in the Garibaldi’s pool when I was six years old.

We’d been floating on our stomachs, but the semi-silence I encountered the moment my ears went under the water was strange and frightening, and I kept standing up again as if I’d forgotten it would be like that.

‘Mummy,’ I’d said. ‘Why can’t we swim in the ocean?’

And my mother held up her hand, two fingers aloft, and said, ‘Quiet now, darling. Mummy has to breathe.’

Yes, I thought, as my head broke the surface, you may be part-fish, mother, and you may have some agreement with the ocean, but even you have to breathe. This is what makes your talent worth having. The crowd watch because they know you have to breathe. And part of them is hoping there might be a spectacle, that you will drown. And now, I think you have, only there was no-one there to see.

Shane’s face peered over the side of the boat. He did not speak. I shook my head. He hauled me over the side and wrapped me in Mum’s towel. It smelt of her; of salt, and tropical laundry powder and something else, something almost ephemeral that brought tears to my eyes.

* * *

It should have been clear that I would not find her, and it’s increasingly clear to me now that no-one will. But the more the cause of her disappearance becomes a mystery, the less it is a tragic accident.

Unless a body washes up, there is no way of knowing what happened. Perhaps she hit her head, or got her fin snagged, or passed out. Perhaps there was a shark. In my head, I imagine her swimming down deeper, gills opening on the sides of her neck. She presse

s her fingers to them in surprise, then takes a fresh gulp of oxygen and paddles down into the darkest part of the ocean.

She is free. The ocean has been waiting for her for a long time.

MISS LOVEGROVE

Her name was Polly Lovegrove.

We all knew her already. She’d been in a long-running television soap opera, and had been the star of every play put on by our local theatre company going back to before I was born.

She was also the director of the first play I ever starred in at university. Our school had a theatre program that only took fifteen people every year, and for most of us, the chance to work with her was the most enticing reason to apply. I was eighteen years old and straight out of high school, a place where I had been told time and time again that I was ‘exceptional’—but at university, I suddenly found myself surrounded by people who were also ‘exceptional’. People who broke into monologues as they spoke to you outside the classroom, people who sang Broadway hits in the cubicle next to yours in the ladies’ room, people who thought knowing Shakespeare plays off by heart was a good party trick. Most of them were thinner than I was, and shorter, and half the time, I felt like a giraffe in roller skates.

At my first lecture, I placed myself in the very centre of the front row just to see her up close. The class was in a drama studio, a large room with scuffed wooden floorboards, black walls and flowing black curtains along three sides of the room. There were no desks and no whiteboard. We sat on the floor. The teacher walked in without looking at any of us and put her notes on a lectern. I was struck by how different she looked out of costume. Without heavy makeup, her eyes were small, and her mouth was sunk deep into her face by lines, something she’d tried to combat with red lipstick. But it was easier to see her clearly from the classroom than from a seat in a dark theatre. Miss Lovegrove had passed the age where she would be cast as the love interest or the heroine. She’d reached the age all actresses reached eventually—soon she would only be cast as the mother.

Well-behaved Women

Well-behaved Women